The modernist conception of urban order is predicated on state regulation of city spaces and social practices. Street food vending disrupts this idealized order and is therefore denounced by state officials and the bourgeois public. Hamstrung by this hostile discursive field and their lack of symbolic capital, how do food vendors manage to maneuver their way through an inhospitable city. In this series, I have made photographs of vendors selling food on the streets of Manek Chowk, arguing that street vendors and city spaces should not be treated as homogeneous categories; differences among vendors and between urban settings are crucial for explaining heterogeneous survival strategies. These differences relate to ethnic identities derived from diverse histories of migration, social structures of class, caste, and gender, as well as to the variegated layout, land use and legal geographies of spaces in the city. By representing street food & the sellers as a valued part of city culture, is it possible for this community to emerge as a new space where the claims of street vendors acquire greater legitimacy in the public sphere, especially when I look from the perspective of modern corporates attempting to dismantle and engulf various intangibles in the name of modernizing economy?

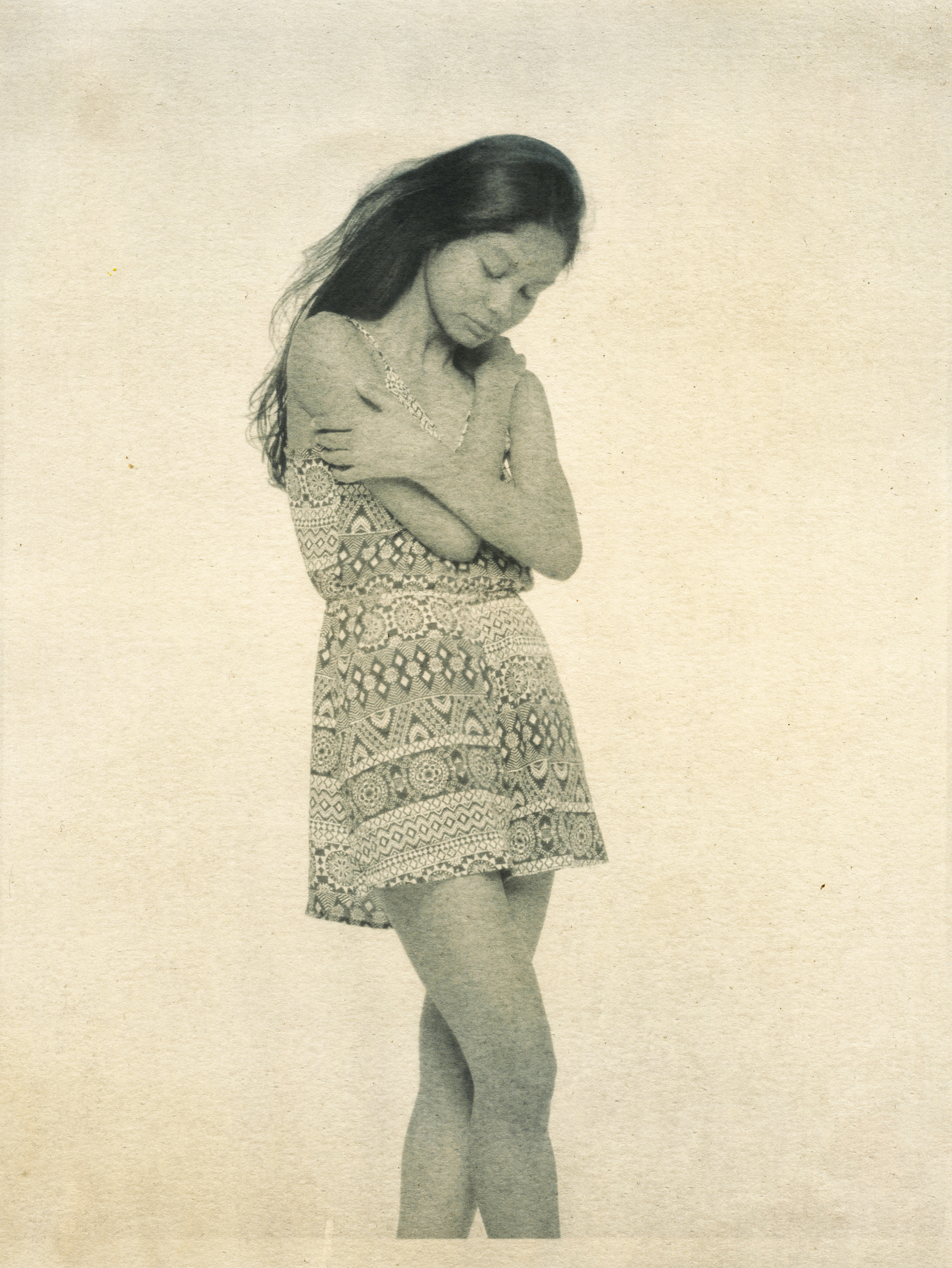

To depict the above, I have made portraits of vendors in their work environment, who sell food in its rawest form. I intend to bring out the nature of the workspace of a community around which the local populace stimulates. The vendor and his workspace are stationed and bring character to the space and that space is as important as any office-goer cabin or more.